The Old Democracy

|

|

November, 2010

By

|

Turkey, and Istanbul in particular, has always been hailed as a confluence of the East and West �€“ where Europe meets Asia over the Bosphoros; where French style bistros and cafes line the streets and share a comfortable space with age old Ottoman mosques; where culture and daily life have evolved into a unique blend of tradition and modernity. On a recent visit to Turkey this idea was reinforced in many ways, and I realized that as unique as this blend is, it is not an entirely new concept or purely a product of Attaturk�€™s vision.

During my time in Istanbul I had the opportunity to revisit some old monuments I had seen many years before. One of these was the Hagia Sophia, a mosque that has now been converted into a museum. The Hagia Sophia, originally a basilica, was filled with frescos of scenes from the bible. Built in 360 A.D., by Constantius II, it served as a cathedral of Constantinople and an epitome of the Byzantine Empire. In 1453, during the Ottoman rule, the Hagia Sophia was converted into a mosque and became the Ayasofya. While the church suffered some destructions during the siege of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks, subsequent rulers, including Suleiman the Magnificent ordered restoration of the structure and added to it with minarets on the outside, and verses of the Koran in calligraphy on the inside. 600 years ago, despite the drive to convert the city to Islam, the Ottoman rulers did not choose to break down the church or destroy its representations of another religion; they simply built around it and along with it. In 1953, Kemal Attaturk declared the building a museum, and in 2006, the Turkish government allowed a back room to be used as a prayer room by both Christian and Muslim staff. Today, this beautiful structure, stands as a symbol of tolerance and respect for the other.

During my time in Istanbul I had the opportunity to revisit some old monuments I had seen many years before. One of these was the Hagia Sophia, a mosque that has now been converted into a museum. The Hagia Sophia, originally a basilica, was filled with frescos of scenes from the bible. Built in 360 A.D., by Constantius II, it served as a cathedral of Constantinople and an epitome of the Byzantine Empire. In 1453, during the Ottoman rule, the Hagia Sophia was converted into a mosque and became the Ayasofya. While the church suffered some destructions during the siege of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks, subsequent rulers, including Suleiman the Magnificent ordered restoration of the structure and added to it with minarets on the outside, and verses of the Koran in calligraphy on the inside. 600 years ago, despite the drive to convert the city to Islam, the Ottoman rulers did not choose to break down the church or destroy its representations of another religion; they simply built around it and along with it. In 1953, Kemal Attaturk declared the building a museum, and in 2006, the Turkish government allowed a back room to be used as a prayer room by both Christian and Muslim staff. Today, this beautiful structure, stands as a symbol of tolerance and respect for the other.

Thousands of miles away in eastern Turkey, on Mount Nemrut, there are ruins of statues erected in 62 B.C. by King Antiochus I Theos of Commagene. The ruling king, paying tribute to the gods, and wishing to be closer to them upon his death, built enormous statues of himself, lions, eagles and those of Zeus, from ancient Greek mythology, and Ahura-Mazda, the almighty of the Zoroastrian faith, believing in their collective power. These statues stand today, as symbol of one man�€™s faith.

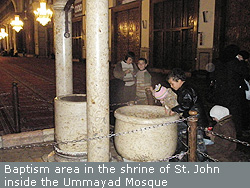

These, and many other examples, bear testimony to the fact that this merging of cultures and religions in Turkey, as well as other countries in the region, is deep rooted in its history. Seeing these monuments reminded me of a similar one, further south from Turkey, in the Syrian capital city, Damascus. The Umayyad Mosque, in the heart of Damascus, is the fourth holiest place in Islam. The mosque was built after the Arab conquest of the region, but recognising the holy significance of the site, parts of the original Christian basilica was left untouched, and today the mosque holds a shrine which contains the tomb of the head of John the Baptist. The shrine, within the Umayyad Mosque, is also a pilgrim destination for Christians around the world, and in 2001 Pope John Paul II visited the shrine. He was the first pope to visit a mosque.

These grand gestures, as lasting as they might be, are difficult to replicate in the present context, though they do stand as a symbol of that unique blend seen in the region, and also as a symbol of the struggles the region faces. Also, it cannot be assumed that these instances from the past are without conflict, for the shift in empires in the region, as elsewhere in the world, was brutal and unforgiving. What is important to learn from the past is the underlying sentiment behind these massive monuments and rulers of yesterday. These structures and many others have survived hundreds of years, and represent the possibility of tolerance and co-existence in the future. What is important to learn is that history, a different kind of history, within the region itself, holds the ideas for the future.

Today the Middle East is infamous for its religious differences, ethnic segregation, and clashes with western ideals. Offers of assistance, solutions to various problems come from all corners of world, adding to their internal struggles. Perhaps, what the region needs to realize is that it already has all the answers and simply look within itself.

Further east at a bend in the Euphrates River, in what was once Babylonia, the small town of Kifl in Iraq, is attempting to preserve its multi-religious history. In the centre of Kifl lies the tomb of Ezekiel, the biblical prophet who preached to the Jews in captivity under Nebuchadnezzar in the sixth century B.C. Kifl has been revered as a holy place by both Jews and Muslims for centuries, and the people of this dusty town have embarked on a path to restore what they term as �€˜the old democracy�€™, of peace and tolerance. The director of the State Board of Antiquities, Qais Hussein Rashid, attempts to promote Kifl and, �€œprove to the world that this place is one of the cultural places that promote civilization and peaceful coexistence between peoples.�€ A difficult task, it has the support of the people behind it, who have no intention of undermining the Jewish heritage of the site, stating that it is their duty to protect it.

In some ways Kifl, in the middle of war-torn Iraq, presents an example for the future, embodying sentiments of the past; where ordinary citizens are attempting to preserve their history, looking beyond religious differences. It is these small, quiet, home grown gestures that could potentially have the power to change the future.

Related Publications

Related latest News

Related Conferences Reports

-

P5 Experts Roundtable on Nuclear Risk Reduction

Download:Geneva Roundtable Report

-

Roundtable on Global Security and Catastrophic Risks

Download:Report on RT revise